The Space Shuttle was a partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program name was Space Transportation System (STS), taken from a 1969 plan for a system of reusable spacecraft where it was the only item funded for development.[4] The first of four orbital test flights occurred in 1981, leading to operational flights beginning in 1982. Five complete Space Shuttle orbiter vehicles were built and flown on a total of 135 missions from 1981 to 2011, launched from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Operational missions launched numerous satellites, Interplanetary probes, and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST); conducted science experiments in orbit; participated in the Shuttle-Mir program with Russia; and participated in construction and servicing of the International Space Station (ISS). The Space Shuttle fleet’s total mission time was 1322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds.[5]

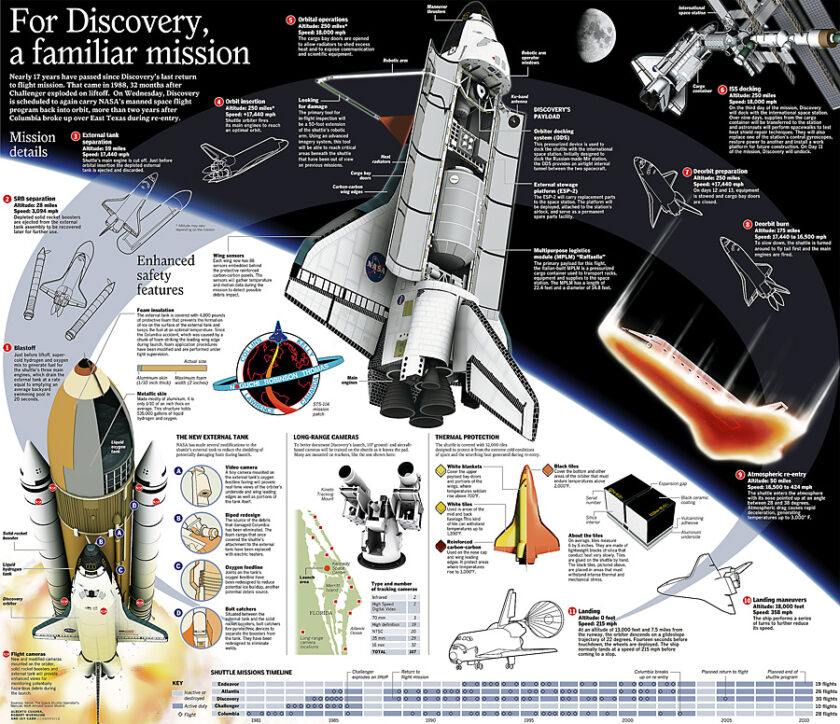

Space Shuttle components include the Orbiter Vehicle (OV) with three clustered RocketdyneRS-25 main engines, a pair of recoverable solid rocket boosters (SRBs), and the expendable external tank (ET) containing liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. The Space Shuttle was launched vertically, like a conventional rocket, with the two SRBs operating in parallel with the orbiter’s three main engines, which were fueled from the ET. The SRBs were jettisoned before the vehicle reached orbit, and the ET was jettisoned just before orbit insertion, which used the orbiter’s two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines. At the conclusion of the mission, the orbiter fired its OMS to deorbit and reenter the atmosphere. The orbiter was protected during reentry by its thermal protection system tiles, and it glided as a spaceplane to a runway landing, usually to the Shuttle Landing Facility at KSC, Florida, or to Rogers Dry Lake in Edwards Air Force Base, California. If the landing occurred at Edwards, the orbiter was flown back to the KSC on the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a specially modified Boeing 747.

The first orbiter, Enterprise, was built in 1976 and used in Approach and Landing Tests, but had no orbital capability. Four fully operational orbiters were initially built: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of these, two were lost in mission accidents: Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003, with a total of fourteen astronauts killed. A fifth operational (and sixth in total) orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. The Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of Atlantis‘s final flight on July 21, 2011. The U.S. relied on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft to transport astronauts to the ISS from the last Shuttle flight until the launch of the Demo-2 mission in May 2020.

During the 1950s, the United States Air Force proposed using a reusable piloted glider to perform military operations such as reconnaissance, satellite attack, and air-to-ground weapons employment. In the late 1950s, the Air Force began developing the partially reusable X-20 Dyna-Soar. The Air Force collaborated with NASA on the Dyna-Soar, and began training six pilots in June 1961. The rising costs of development and the prioritization of Project Gemini led to the cancellation of the Dyna-Soar program in December 1963. In addition to the Dyna-Soar, the Air Force had conducted a study in 1957 to test the feasibility of reusable boosters. This became the basis for the aerospaceplane, a fully reusable spacecraft that was never developed beyond the initial design phase in 1962–1963.[6]:162–163

Beginning in the early 1950s, NASA and the Air Force collaborated on developing lifting bodies to test aircraft that primarily generated lift from their fuselages instead of wings, and tested the M2-F1, M2-F2, M2-F3, HL-10, X-24A, and the X-24B. The program tested aerodynamic characteristics that would later be incorporated in design of the Space Shuttle, including unpowered landing from a high altitude and speed.[7]:142[8]:16–18

Main article: Space Shuttle design process

In September 1966, NASA and the Air Force released a joint study concluding that a new vehicle was required to satisfy their respective future demands, and that a partially reusable system would be the most cost-effective solution.[6]:164 The head of the NASA Office of Manned Space Flight, George Mueller, announced the plan for a reusable shuttle on August 10, 1968. NASA issued a request for proposal (RFP) for designs of the Integrated Launch and Re-entry Vehicle (ILRV), which would later become the Space Shuttle. Rather than award a contract based upon initial proposals, NASA announced a phased approach for the Space Shuttle contracting and development; Phase A was a request for studies completed by competing aerospace companies, Phase B was a competition between two contractors for a specific contract, Phase C involved designing the details of the spacecraft components, and Phase D was the production of the spacecraft.[9][8]:19–22

In December 1968, NASA created the Space Shuttle Task Group to determine the optimal design for a reusable spacecraft, and issued study contracts to General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, and North American Rockwell. In July 1969, the Space Shuttle Task Group issued a report that determined the Shuttle would support short-duration crewed missions and space station, as well as the capabilities to launch, service, and retrieve satellites. The report also created three classes of a future reusable shuttle: Class I would have a reusable orbiter mounted on expendable boosters, Class II would use multiple expendable rocket engines and a single propellant tank (stage-and-a-half), and Class III would have both a reusable orbiter and a reusable booster. In September 1969, the Space Task Group, under leadership of Vice President Spiro Agnew, issued a report calling for the development of a space shuttle to bring people and cargo to low Earth orbit (LEO), as well as a space tug for transfers between orbits and the Moon, and a reusable nuclear upper stage for deep space travel.[6]:163–166[4]

After the release of the Space Shuttle Task Group report, many aerospace engineers favored the Class III, fully reusable design because of perceived savings in hardware costs. Max Faget, a NASA engineer who had worked to design the Mercury capsule, patented a design for a two-stage fully recoverable system with a straight-winged orbiter mounted on a larger straight-winged booster.[10][11] The Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory argued that a straight-wing design would not be able to withstand the high thermal and aerodynamic stresses during reentry, and would not provide the required cross-range capability. Additionally, the Air Force required a larger payload capacity than Faget’s design allowed. In January 1971, NASA and Air Force leadership decided that a reusable delta-wing orbiter mounted on an expendable propellant tank would be the optimal design for the Space Shuttle.[6]:166

After they established the need for a reusable, heavy-lift spacecraft, NASA and the Air Force determined the design requirements of their respective services. The Air Force expected to use the Space Shuttle to launch large satellites, and required it to be capable of lifting 29,000 kg (65,000 lb) to an eastward LEO or 18,000 kg (40,000 lb) into a polar orbit. The satellite designs also required that the Space Shuttle have a 4.6 by 18 m (15 by 60 ft) payload bay. NASA evaluated the F-1 and J-2 engines from the Saturn rockets, and determined that they were insufficient for the requirements of the Space Shuttle; in July 1971, it issued a contract to Rocketdyne to begin development on the RS-25 engine.[6]:165–170

NASA reviewed 29 potential designs for the Space Shuttle, and determined that a design with two side boosters should be used, and the boosters should be reusable to reduce costs.[6]:167 NASA and the Air Force elected to use solid-propellant boosters because of the lower costs and the ease of refurbishing them for reuse after they landed in the ocean. In January 1972, President Richard Nixon approved the Shuttle, and NASA decided on its final design in March. That August, NASA awarded the contract to build the orbiter to North American Rockwell, the solid-rocket booster contract to Morton Thiokol, and the external tank contract to Martin Marietta.[6]:170–173

Jared Owen

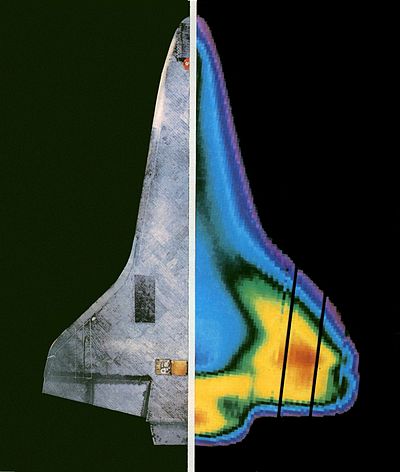

The Space Shuttle thermal protection system (TPS) is the barrier that protected the Space Shuttle Orbiter during the searing 1,650 °C (3,000 °F) heat of atmospheric reentry. A secondary goal was to protect from the heat and cold of space while in orbit.[1]

Discoveries that sustained the American Space Program are enormous leaps in the production of material sciences. They have helped pave the way for human evolution.

Space science—science performed from vehicles that travel into Earth’s upper atmosphere or beyond—covers a broad range of disciplines, from meteorology and geology, to lunar, solar, and planetary science, to astronomy and astrophysics, to the life sciences.

A relatively young field, space science blossomed in the latter half of the 20th century, so the Museum’s collection focuses mainly on that period, and especially on objects flown in the atmosphere or in space. The space science objects on display include vehicles (balloons, sounding rockets, satellites, space probes, orbiters, landers), the scientific instruments they carried, and ground-based instruments or other examples of technology that support space science or illuminate its development, nature, or history.

. A church...

. A church...